Stuffy air in schools.

In many classrooms, the air leaves much to be desired. A survey conducted by robatherm shows clearly: We do need climate change in classrooms.

The key to successful learning is acknowledged to be multifaceted. One of these facets is a favorable environment. What tends to be all too easily over[-]looked is that air quality in the classroom plays a decisive role. Relevant studies and teachers' surveys have shown us an acute need for action concerning indoor conditions in many German schools. During the pandemic, the issue came into focus because of the risk of infection through aerosols. However, even after COVID-19, the core problem isn't going to disappear into thin air. Classrooms need climate change. robatherm sheds light on essential facts and outlines a modern solution to enable schools to breathe a sigh of relief.

The present situation sets a clear priority: Schools are focusing on preventing infections with the SARS-CoV-2 coronavirus. In the process, mobile air purification devices have also been put up for discussion. However, their effi[-]ca[-][-]cy and performance capacities for classrooms are very controversial. In response to the need, schools are now utilizing a means of combating the virus' transmission as simple as effective: breaks for ventilation. Airing out works temporarily, but the permanent interruptions in teaching bring about new problems – uncomfortable temperature fluctuations, distracting commotion, constant new dis[-]cussions. In a 21st-Century school system, that kind of fresh air supply seems outdated and somewhat futile. Therefore, the measure is more likely to become a complementary part of the solution.

Light material that makes learning difficult

The fundamental problem lies in the composition of “used” indoor air. As a natural decomposition product of human respiration, carbon dioxide (CO₂) is an essential air quality indicator. While only about 400 ppm CO₂ is measured outdoors, it is not uncommon to often reach a multiple of that concentration in unventilated classrooms. We are talking about stuffy air. After all, the presence of so many students and teachers, which lasts for hours on end, quickly raises the CO₂ content in enclosed classrooms to alarmingly high levels. Findings on the effects of elevated CO₂ levels are by no means something new.

As early as 1858, the hygienist Max von Pettenkofer stated that the concentration of carbon dioxide in schools should not exceed one per mille (equivalent to 1,000 ppm). This threshold value for rooms where teaching and learning take place is still valid today. In this regard, some studies on this are both noteworthy and alarming. Measurements at schools have revealed that a CO₂ concentration of 2,000 ppm is often exceeded within just the first two hours of teaching in unventilated classrooms. The German Federal Environment Agency has classified the values of this scale as “hygienically unacceptable”.

The same applies to carbon dioxide:

concentration makes all the difference. Too much CO₂ can cause performance-diminishing symptoms that no one wants. Especially not in school:

- Impaired perception

- Weakened attention

- Reduced power of concentration

- Impaired cognitive ability

- Weakness in drive

- Change in social behavior

Hot on the trail of CO₂

The reasons for rapidly deteriorating indoor air quality are quite complex. One crucial factor is the air space available per room occupant. A ratio is drawn between the classroom's volume and the number of occupants to determine that factor. According to a study carried out in North Rhine-Westphalia (involving 363 classrooms in 111 schools), students in elementary, middle, and high schools have fewer cubic meters of air space available than classrooms in special needs or vocational schools. The deviations in the average CO₂ concentration are accordingly large. This is because where more people share less space, the air is “used up” more quickly. Also, the length of time spent in a room and the people's activity play a decisive role. Suppose one considers the high number of students present in classrooms for long periods. In that case, the root causes of the CO₂ problem become quite clear.

Good indoor climate – better classroom climate

Breaks for ventilation are the first important step to overcome this dilemma. When the CO₂ concentration in the room is reduced, the student's attention to the subject matter increases. Therefore, a regular supply of fresh air improves the room climate and the learning climate. Oral participation is intensified, and students show more interest in discussions. Clearly, such a scenario also reduces stress levels among teachers. This is a win-win situation for everyone. A more relaxed atmosphere noticeably improves the quality of teaching and learning success.

Breathing a sigh of relief thanks to ideal air conditioning

As sensible as regular airing in schools may be, it cannot be the sole permanent solution. The effects are too short-lived, and the side effects are too disruptive. Instead, sophisticated ventilation and air-conditioning measures are required, which don't distract anyone from what's happening in the classroom. Instead, they continuously ensure an indoor climate that is conducive to studying. Because air handling units not only provide a constant exchange of air, they also control the temperature and regulate airflow. These systems also control the temperature, regulate humidity and filter out pollutants. In many modern school buildings, the reliability of such systems can already be felt and measured daily. One of many examples that robatherm can point to is the Diedorf High School, which was awarded the German Architecture Prize, among others.

Inquired: How do teachers evaluate the air in schools?

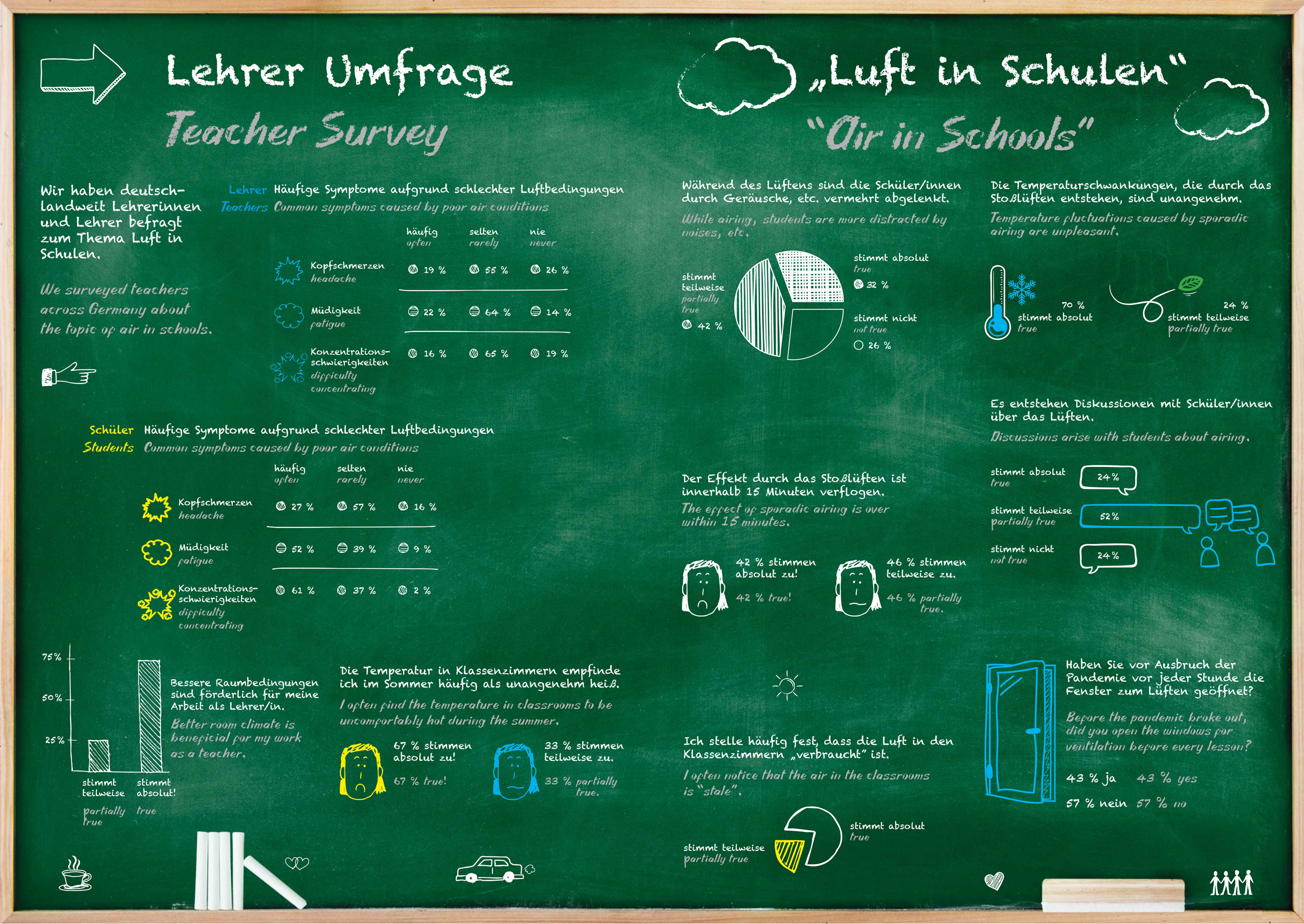

As a specialist for air handling units, robatherm wanted to know first-hand. In light of the Corona pandemic, 50 teachers from various schools were interviewed about their perception of indoor air quality and their personal observations of how their schools are ventilated. Although this is only a sample of the current situation, the results paint a fairly clear picture: thanks to the ventilation break, most teachers feel a bit more protected. Sporadic airing usually lasts around five minutes. However, the majority of the respondents complained about the students' resulting distraction and the frequent temperature fluctuations in the classroom. Also, 88% of the respondents feel that sporadic airing's positive effect is only noticeable for a short time. Regardless of the current pandemic situation, almost all teachers surveyed frequently perceive “stale” or “stuffy” air in the classroom. Many see their teaching impaired by the prevailing conditions at their school. Overall, this report card shows room for improvement.

Overview of the main results of the robatherm survey: